Staying Home and Not Working Makes People Sick

It has become one of the Great Questions of Our Age: Why have so many prime-age American men dropped out of the labor force? The percentage of American men ages 25 through 54 who are neither working nor looking for work has been growing for decades. In September, it was 11.4 percent -- which is down from the all-time peak of 12.1 percent in October 2013, but still almost quadruple the level of the early 1960s.

I wrote last week about Nicholas Eberstadt's new book on this topic, which looks into several possible explanations but puts the biggest emphasis on what Eberstadt calls the "incarceration explosion" of the 1980s and 1990s. On Friday, Bloomberg Businessweek's Peter Coy reported on new research by Princeton University economist Alan Krueger that explored another possibility -- maybe men have given up on working or looking for work because they really don't feel good.

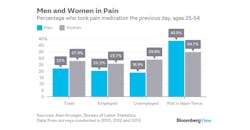

“Nearly half of prime age NLF [not-in-the-labor-force] men take pain medication on a daily basis, and in two-thirds of cases, they take prescription pain medication,” according to Krueger’s paper, Where Have All the Workers Gone?

It's a pretty stunning statistic, but what exactly does it mean? Here are the numbers in some context, courtesy of Krueger:

Overall, men are less likely to be taking pain medication than women. But men who have dropped out of the labor force are much more likely to be taking pain meds than either other men or the women who've dropped out.

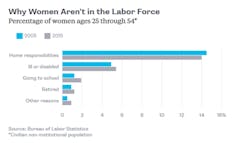

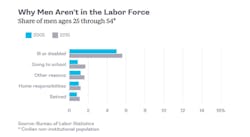

To understand why that is, it's helpful to know why people have dropped out of the labor force. And whaddya know -- the Census Bureau asks that in an annual supplement to the survey that's used to determine the unemployment rate. Last December, Steven F. Hipple of the Bureau of Labor Statistics gave a detailed accounting of what respondents said in 2004 and 2014. Here are the key 2005 and 2015 numbers, courtesy of Hipple. First, for women:

The main reason -- by far -- that women drop out or stay out of the labor force is because of home responsibilities: taking care of kids, aging relatives and such. That's not at all the case for men.

Most women who aren't in the labor force are still working, just not for pay. Most men who aren't in the labor force simply aren't working. So it's a different and smaller (albeit growing) population. It's also a pretty unhealthy population, with half of the men not in the labor force in 2015 reporting that they were ill or disabled. Interestingly, the ill-or-disabled percentage of the overall prime-age population wasn't all that much higher for men (5.6 percent) than for women (5.4 percent).

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, about 97 percent of prime-age men either had jobs or were actively looking for them. Work has gotten less hazardous and physically demanding since then, not more. So how can it be that 5.6 percent of prime-age men report being out of the labor force now because of illness or disability, while only 3 percent were out of the labor force for any reason in the early 1960s?

Some of this may be because our definitions of illness and disability have changed and expanded over time. I've got to think that a lot of it, though, is because long-term unemployment and inactivity make people sick. Those without jobs are less likely to have access to health care. They're also less likely to lead active lives. According to Eberstadt's analysis of government time-use data, men who aren't in the labor force spent an average of five and a half hours a day watching television and movies in 2014, compared with about two hours a day for working men and three and a half for unemployed men. That's not exactly healthy.

It seems like vicious cycle. Men who drop out of the labor force -- maybe initially for health reasons, maybe not -- fall into lifestyles that render them ever less capable of rejoining it. (This may be true of a lot of women, too, but their characteristics are harder to nail down because of the split between those who are truly out of work and those with home responsibilities.) Getting them back into the labor force seems like it ought to be a national priority. But it's not going to be easy.