Pennywise: Copper Making More Sense in Manufacturing Design

Authors: Susanne Barton, Mark Burton and Laura Millan Lombrana

The world’s biggest mining companies would like you to put more zinc in your zucchini and copper in your socks and dental floss.

While builders and manufacturers remain the biggest metals users, producers are confronting the end of a Chinese industrial boom that fueled surging global demand and prices. For more than a decade, the country dominated markets as it sucked up raw materials to build factories, homes and power lines. Now, with the industrial engine cooling, mine owners are looking for new uses to spur sales like in fertilizer, electric-car batteries and salmon cages.

“Traditional demand isn’t going to fall off a cliff,” said Paul Gait, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein Ltd. in London. “But it’s true that no one wants to hear about industrial production growth or Chinese cement demand anymore.”

Mining companies have toyed with exotic uses for years, but the search took on new urgency as the economy began to mature in China, the world’s biggest buyer of metals. This year, the country will have its slowest growth in copper use in a decade, Barclays Plc analysts said last month. Base metals including aluminum and nickel are heading for their first quarterly decline in more than a year. In May, Moody’s Investors Service downgraded China’s sovereign debt, sparking concern that tighter credit will hurt smokestack industries.

Fixed asset investment trailed estimates last month as the country’s property market cooled and the country sought to rein in credit, data showed Wednesday.

China consumed almost half of the world’s refined copper in 2014 as the country’s demand surged 8.8% from a year earlier, Barclays estimates. Since then growth has been slowing, and by 2020 the bank estimates China usage will increase just 1.5%. The economy that was growing at double-digit rates through most of the 2000s has slowed every year since 2010 to about 6.7% last year, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

That’s forcing company executives to focus on ways to bolster future growth.

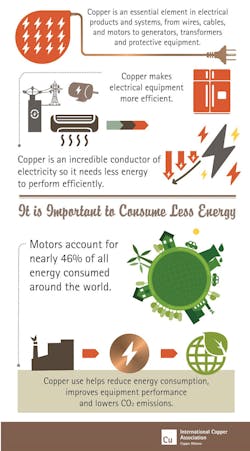

“There is a huge opportunity for metals such as copper, from developing batteries to store renewable energy, to the copper motor rotor used” in Tesla Inc. electric vehicles, said Robert Dwyer, associate director of environment at the Copper Alliance.

Codelco, Chile’s state-owned mining company and the world’s largest copper producer, has promoted using the metal in hospitals, airports and even socks -- 1.4 million pairs sold last year in Chile. The company has invested about $10 million in new applications over the last five years, according to Sebastián Carmona, interim head of Codelco’s technology arm.

The mine owner also has encouraged innovation with $50,000 grants to entrepreneurs, including antibacterial baby clothes, dental floss with copper nano-particles and a copper-based material that can be used for 3D printing of orthopedics.

New uses are also being developed for aluminum. Arconic Inc., a maker of aluminum parts for cars and planes, is investing in facilities to support the use of metals by three-dimensional printing machines, which use computer software to manufacture products.

3-D Printing

After a slow start, usage of aluminum is growing in 3-D printing, along with titanium, cobalt and chrome, as the technology moves products out of testing and into commercial use in industries like aerospace, said Terry Wohlers, the founder of industry consultant Wohlers Associates in Fort Collins, Colorado.

About $542.2 million of 3-D printers for metals were sold last year, or 9% of all sales, Wohlers estimates. By 2022, sales will increase more than fourfold to $26 billion, and with machines devoted to metals growing faster than the industry overall, he said.

Sales are growing for zinc-infused fertilizers from companies including Mosaic Co., especially after a 2008 study estimated 450,000 children under the age of five die each year from zinc deficiency.

Adding zinc into fertilizers could consume as much as 600,000 tons of the metal -- or about 4% of global demand -- in “the not too distant future,” Don Lindsay, the chief executive officer of metals producer Teck Resources Ltd., said at a conference last month.

At the same conference, Glencore Plc boss Ivan Glasenberg promoted the idea that his company mines minerals like cobalt, nickel and copper needed to build the growing number of electric vehicles.

If 95% of the world’s auto sales are electric vehicles by 2032, the industry would need 20 million tons of copper annually -- roughly equivalent to usage in every other application combined in 2016, Glencore estimates. For cobalt, that scenario would mean an increase in demand of 679,000 tons, or 5 1/2 times of what the world produced last year.

Expanding Capacity

Manufacturers in China aren’t taking any chances. Production capacity for copper foil -- a component in the anodes used in lithium-ion electric vehicle batteries -- is set to double within the next two years as 15 new manufacturing plants ramp up, according to the International Copper Study Group.

Metal producers should take their cue from the aluminum industry to prepare for changes in demand, Bernstein’s Gait said. When oversupply left prices low, aluminum producers invested in downstream ventures to promote the lightweight metal as a substitute for steel and copper in such products as autos and electrical wiring.

“Aluminum isn’t really the best material for these kinds of applications,” Gait said. “But when they found no one wanted to buy their commodity, producers went out and bought downstream assets to develop competitive products themselves. Other miners could certainly benefit from taking those kinds of opportunities more seriously.”