The Curious Case of the Missing Pay Raises

One element is missing in an otherwise strong U.S. job market: Ample hiring still isn’t translating into similarly ample wage gains, particularly for those in the middle of the pay scale.

Overall, the employment report for March portrayed an economy running at or close to capacity. Nonfarm employers added an estimated 211,000 jobs in April, bringing the three-month average to 174,000 -- plenty to bring down the unemployment rate, which fell 0.1 percentage point to 4.4 percent. That's below what Federal Reserve officials consider "full employment," the point beyond which inflation tends to become a problem.

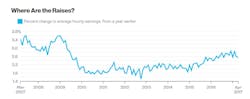

Yet for all the signs of strength, workers aren’t seeing the kinds of raises they have known in the past. Although various indicators suggest wage growth has been accelerating, average hourly earnings were up just 2.5 percent from a year earlier in April, close to a percentage point short of the pace that prevailed before the last recession. Here's how that looks:

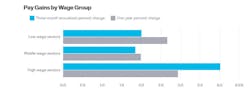

The weakness has been concentrated in middle-wage industries, such as durable goods manufacturing, construction, health care and education. During the past three months, hourly earnings in this wage group have increased at an annualized pace of about 1.8 percent. That compares with 2 percent for low-wage occupations (such as retail, leisure and hospitality) and 4 percent for high-wage occupations (such as professional services, finance and information technology). The picture is similar during the past year, albeit a bit better for the low-wage group. Here's a chart:

Persistent demand for workers may eventually push up pay. That said, it's not clear the gains can match the pace of previous expansions. In the longer term, wages can rise faster than consumer prices only if employees produce more for each hour worked. But labor productivity has been growing at an average annual rate of just 0.6 percent in the past 5 years, hardly enough to justify even the current pace of wage growth.

One hope is that the little wage growth there is will prompt companies to make more productivity-enhancing capital investments to offset increasing labor costs. In an encouraging sign, investment rose sharply in the first three months of this year after a long period of decline. It remains to be seen, though, whether that turn will become a trend.

The infrastructure investments that Donald Trump has promised could also help boost productivity, by improving the roads, pipes and grids that facilitate and power commerce. Lately, though, the president has focused more on tax cuts that economists doubt will have such a capacity-expanding effect.

In short, barring a lucky break, middle-wage Americans could be facing a lot more disappointing paychecks.