With a penchant for wearing Aviators and draping themselves in Old Glory, Megabots, Inc. co-founders Gui Cavalcanti and Matt Oehrlein's public personas scream brash, unflinching American bravado. That's by design, of course. Why build a 16-foot tall, 10-ton, two-seater robot tank if you don't have some swagger?

And why build a giant robot with cannons for arms and Caterpillar treads for feet if you're not going to put them to good use trying to demolish someone else's iron giant?

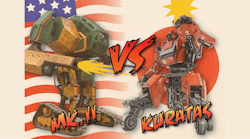

So in this instance, it made perfect sense for Cavalcanti and Oehrlein to dress like Apollo Creed and challenge the only other robot of its kind: the Japan-based Suidobashi Heavy Industries' Kuratas, to an epic fight.

In a YouTube video posted in June 2015, the pair outline the details for the fight:

The Japanese roboticist intended to sell Kuratas for about $1.35 million each, according to The Verge. Even the 3,000 people who placed orders thought it was a joke, and none were honored.

So when MegaBots challenged Kurata, the artist/designer responded in Japanese, "Yeah, I'll fight."

His only demand was that the fight be hand-to-hand, as sticking giant guns on a machine is "super American."

He's not wrong. The Mk. II, which will be driven by Cavalcanti, as Oehrlein mans the guns, does display some bombastic firepower. These include air cannons that can launch giant paintballs and t-shirts. Team USA—whose brainpower has been bolstered by NASA, Parker Hannifin, and more—now needs to design its 350-horsepower mech to throw a punch.

Even if the Mk. II loses the fight, MegaBots still wins. This bout, they hope, will lead to a new technology driven amalgamation of UFC, NASCAR, and Transformers, and that plan has attracted more than $2.4 million from investors.

"We want to make a sport out of it: Monday Night Football, then Tuesday Night MegaBots," explains Cavalcanti, a mechanical engineer who previously worked at Boston Dynamics, the maker of Atlas, a bipedal robot that can walk over rough terrain.

"That's the impact we're looking to have. And we really think it will drive interest in STEM careers. "

STEM—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—comprises the disciplines American students seem to be falling behind in, even as these become more important to economic growth in a competitive global battlefield.

"The education in American junior high schools, in particular, seems to be a black hole that is sapping the interest of young people, particularly young women, when it comes to the sciences," writes Thomas Friedman in the book, The World Is Flat.

The U.S. finished 35th out of 64 countries in math and 27th in science in the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which tests 15-year-olds.

"For every dollar of manufacturing value-added, it generates $3.60 worth of economic activity throughout the rest of the American society," says Stephen Gold, president and CEO of Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation Foundation (MAPI). Based off a 2016 study done by MAPI and the University of Delaware, this impact more than doubles the previously thought $1.40 impact.

That dollar value ties directly to job creation in other sectors, such as service and transportation. Gold's data says that 3.4 more people are employed for every one manufacturing job.

"The technology industry is far more effective at creating additional labor requirements in other parts of the economy, and can be as many as six," he says.

But manufacturing employment, once the economic backbone of the country, has withered and slunk since a peak posture of 19.5 million jobs in 1979. Last year, that number hunched at 12.3 million, a drop of 37%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The unsettling thing is the population is 93 million higher, too. In 1979, 8% of the entire population was employed in manufacturing; now it's 3.8%.

It's no coincidence that this decline started at the same time Japan began to invest heavily in industrial robots. While General Motors was paying pensions for workers who retired at age 48, Japan only needed to pay for robots' initial cost and upkeep.

"A number of those [automotive] jobs could have been saved if they would have invested in automation instead of shutting it down and chasing low cost labor," asserts Jeff Burnstein, president of the Robotic Industries Association.

Gundam Style

While the MegaBots team has nothing to lose, the Kuratas side has wagered Japan's very honor.

"We can't let another country win," Korgoru says confidently in the rebuttal video. "Giant robots are Japanese culture."

And the reason for that is because robots are a giant part of Japan's economy.

Demand for industrial robots in Japan jumped from 4,000 in 1975 to 21,000 in 1981, and nearly doubled to 39,000 in 1985, according to the book Innovation in Japan.

During this spike in automation, Japan became enamored with its newest workforce and automation in general, and their culture reflects this, from high-tech toilets to animatronic tour guides.

Long before Kuratas, in 1979, there was an anime called Mobile Suit Gundam. In this animated dystopia, nations solved their problems with giant piloted robots. It spawned several series and imitators.

Kogoru says one such anime inspired him to build Kuratas.

"When I was a kid, I thought there were going to be giant robots in the future," he told The Verge in 2012. "But no matter how long I waited, people were only able to make small robots, like Asimo. Eventually, I thought 'I can't wait anymore,' and set out to make one myself."

American kids also ate up any and every giant robot anime Japan churned out. There was a Honda or Toyota in nearly every suburban garage and a Transformer in every playroom. You knew whose parents lost their jobs to Japanese robots because they had GoBots, the inferior knockoffs.

This was the world Gui Cavalcanti and Matt Oehrlein were born into, both in May 1986, just months before little boys everywhere would see their best red, white and blue role model, Optimus Prime, perish in The Transformers: The Movie.

Image: Hasbro

This may have been the seminal giant robot moment of most young boys' lives, but it would not be the last. The British Invasion had the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Led Zeppelin; this Japanese Invasion featured Robotech, Voltron, and Power Rangers.

The robots American children fantasized about were no longer the wimpy personal assistants of the 1950s and '60s, like Robbie the Robot from Forbidden Planet or B-9 from Lost in Space. They were metal giants that you could steer like a car, with the added option of fusing with friends to create even an bigger giant robot. And everybody had a flaming sword.

This might seem like a nightmare for manufacturing's old guard, many of whom survived the horrors of World War II, or Korea, or Vietnam, who learned their craft working on a tank or bomber. For their children and grandchildren, though, it's a dream come true.

A Dream Deferred

"You grew up hoping that the giant battles of science fiction would become real, and we did too," Oehrlein barks as he solders some wires in a Kickstarter video intended to drum up financial support to upgrade Mk. II. "That dream is one year away."

The video, posted to the crowdfunding site in August 2015, raised more than $550,000, from nearly 8,000 people. Every major tech magazine, from Wired to Popular Science ran copy. It seemed everyone wanted in on the moment.

It's been more than a year and that moment hasn't happened yet.

It appears the logistics of making and moving a behemoth, battle-ready Mk. III—the new version—from MegaBots headquarters in west Oakland to the undisclosed arena (most likely at an international location), has taken longer than expected.

Screengrab: MegaBots/ YouTube

They haven't released an actual date yet, though they did give a pretty logical explanation.

"We're planning an event in which people are piloting multi-ton combat robots that are trying to destroy each other, without harming the pilots, and that takes a lot of careful consideration," the MegaBots team released in a July update.

And most details, they say, couldn't be communicated due to a non-disclosure agreement with Suidobashi.

That initial brashness is what makes America great, though. John F. Kennedy did the same thing when he announced in May 1961 that an American would safely make it to the moon by the end of the decade. That's eight more years than MegaBots gave itself.

While the team probably shouldn't have harnessed themselves to such a deadline given all the variables, saying the duel would take place somewhere, sometime probably wouldn't have garnered the worldwide attention.

When the gauntlet was first thrown, MegaBots had a handful of employees to design, engineer, fabricate, and market a heavy piece of machinery powerful enough to destroy a high-tech robot made by a highly advanced society obsessed with giant fighting robots, yet safe enough for the co-founders not to get crushed on live television.

That was 2015. MegaBots is no longer crowdsourcing but getting actual investors. It has raised more than $3.8 million from investors including Autodesk, AME Cloud Ventures, and Azure Capital Partners, and reportedly $1 million more from speaking engagements and appearances.

NASA is their safety consultant and William Morris Endeavors, the super agency that represents the NFL and NHL, as well as owning the UFC, now run the entertainment and marketing side.

But money and publicity only get you so far. Sooner or later, MegaBots' mettle will be tested in the ring, or octagon or dodecahedron or wherever they fight.

And for that, the company has assembled with some of America's finest engineering minds to get the Mk. III ready to rumble.

Fight Club

It's early September, and Jeff Falkowski walks across the warehouse courtyard, dodging welding sparks and passing giant boxes, tubes and layers of sheet metal and stops before the hulking hybrid weapon/ heavy equipment. Its battered torso a mix of dented forest green steel and clay red armaments; its legs possibly scavenged from an old abandoned excavator.

Then Cavalcanti hops in and start rolling the machine toward the middle of the courtyard, moving it through a range of motions for the Parker Hannifin marketing communications manager.

Falkowski had seen the Mk. II a few months before to talk hydraulics with MegaBots, but the robot was supine, having been flipped by a forklift after sparring with wrecking a ball.

"It was pretty impressive, particularly at full height," Falkowski says. "You get a sense of how much power it takes to move around a piece of equipment that large. And it's going to fight another robot of that size."

Falkowski calls Cavalcanti and Oehrlein "engineering geniuses," but he knew Parker — a world leader in motion control components — could still help Team USA.

Instead of musculature, the Mk. II's movements are powered by hydraulics, making Parker the perfect strength and conditioning coaches.

"It's not just brute force, there's some thinking behind it, too," Falkwoski says. "They created the controls to tell it to make it moves like a human. Now it's up to us to help them figure out how to make the arms move naturally."

One factor is placement of hydraulic hoses.

"If you disable the right part of the hydraulics, you can shut down the robot all together, especially taking away whatever weapons they're using," Falkowski says.

For the crowd's sake, MegaBots hopes their will be robot blood, a.k.a. hydraulic oil.

"You don't want hoses to fail in a spectacular fashion on a construction site," Oehrlein says, "but it's not necessarily a bad thing [during the fight with Kuratas], as long as it's even."

So Parker has worked to protect the hydraulics plant, while positioning fittings for best range of motion, hose guards to contain ruptures, and abrasion resistant hose sleeves to prevent tears, all the things to make it "as durable, agile, and safe as it can be," Falkowski says, adding, "A pin prick rupture can pierce skin."

Why would a multi-billion dollar company get so involved with a small robot startup?

"A, giant robots are cool, and B, because we think there is some growth potential for what they do," Falkowski says. "Most people don't get real excited about hydraulics and pneumatics, but we do at Parker. This is an opportunity to show motion control can actually be really interesting. You can mix fun and science, and that's something we'd love to be involved in."

The reason Parker has visited Megabots headquarters today is more to check on its latest, maybe most important contribution: the ParkerStore OnSite Container.

Optimus Prime hauled a container for weapons; MegaBots has one for repairs.

Photo: Jeff Falkowski/ Parker Hannifin

And while most of what MegaBots does is a mystery, this is one weapon that doesn't have to remain secret.

"It has everything we need for building out as quickly as possible," Cavalcanti says. "We're already using it to make hoses, the track base, and new potential weapons. It's really a game changer. Our turnaround time went from up to a week to right now. To cut up a hose and attach fittings takes a couple of minutes to an hour."

The 20-ft space holds reels of hoses up to 2-in. diameter, fittings, a cutting saw, crimper, racks, and bins, all in an air-conditioned, lit space. A vendor-managed inventory program ensures the container stays stocked.

Check out the ParkerStore Onsite Container specs on our directory side.

"They are outfitted with pretty much everything you need to be a mobile hose assembly fabrication shop," says Falkowski, adding that any facility can get the same set up on the shop floor if they have comparable room.

First used in 2011, these leased units are used in mining, forestry and construction operations, where it's not efficient to drive somewhere to pick up new hoses when an excavator hose fitting busts, especially if you're out in Northern Canada's tar sands.

"The key thing for the customer, it all comes down to downtime," Falkowski says. "It's too expensive to operate without spares being handy, and that could cost hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars."

Managing every dollar and every day is vital to MegaBots' success, as public interest and sponsorships could wither if they fail to stoke the embers of excitement.

At events like the upcoming MegaDay in the Bay area, people will want to see the giant robot move, and the OnSite Container guarantees that's always possible.

"In the past, if we'd blow a hose before we do an appearance, we'd go to super emergency 24/7 hose making guys, who usually repair aircraft," says Oehrlein, who had to call such a service last Thanksgiving. "Instead of using this multi-thousand dollar hoses service on a holiday, now we can just go to the container and make one up."

The other major factor is the training for the actual fight. To prepare for Kuratas, MegaBots has to beat the crap out of their prototype. Like a fighter, you want to be able to tape up the bruises and get back out there.

"It gives us the ability to battle test our design right at our own facility," Cavalcanti says. "Let's see how hard it is to rip this arm off. Does it cut the hydraulic hose? We can test that and we have backup parts to repair it and try something different within the same day. It really accelerates being able to design a better weapons system, a better armor system onsite."

Mecha Messiahs

Like Oehrlein, Cavalcanti played MechWarrior, and immediately joined the pre-STEM robotics club called FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) when it was offered in his high school.

The founder of this club is Dean Kamen, known for the Segway and iBot wheelchair.

"I want to compete for the hearts and minds of kids with the excitement of the Super Bowl," he said at FIRST's inaugural robotics competition in 1992.

Photo: FIRST

Sound familiar? It's the same plan MegaBots has, but was he wearing an American flag cape and walking away from an explosion as he said it?

No, no he wasn't, but even so, what started as a tournament of 100 kids has grown to 400,000.

Now one of his acolytes has upped the ante by scaling the robot competition from 10 lb to 10 tons.

And trying win the hearts and minds of kids is a hell of a lot easier with a 10-ton robot that has a chainsaw for a hand.

Adults might find this wildly dangerous, but it's exactly what children still want. Giant fighting robots never go out of style. Voltron just got rebooted on Netflix, a new big budget Power Rangers movie arrives in 2017, and Robotech could follow in a few years.

Image: Lionsgate

But all these bots are piloted by humans, and it's the people behind the Mk. II who will drive this fight, and the future sports league.

"It's one thing to see two robots fight each other, but then to understand the personality driving them behind this whole effort is what will make it most interesting," says Falkowski. "That's what makes you care about Rocky."

This training portion is on full display on the MegaBots new web series, which will give viewers a truer sense of a demanding industrial production schedule than shows constrained by television like Mythbusters, Cavalcanti says.

Because this is a web series streamed on MegaBots' Facebook page and YouTube channel, it opens up this previously unknown magical world of science and engineering to anyone with an Internet connection.

Of course the fight itself will get most of the headlines, and whether the American underdog can score one for the steel and auto workers who foreign robots made obsolete is great story.

But what happens next? What if this league takes off and American children become as obsessed with designing and fabricating robots as they are evolving their Pokémon?

"That future America would remain as the innovation hub of the world," Gold answers. "We'd have the most highly skilled workforce, the most innovative companies would be here, and countries around the world would continue to invest in America. There'd be higher economic growth and higher living standards."

So is the whole point of this that America could go from mediocrity, which over a few generations could quickly turn to obscurity, back to the top because of a live action Rock 'Em Sock 'Em Robot match?

Yes and no. Unless we do someday turn to a Gundam-type global power system, one robot fight won't change the nation overnight. But what it could do is inspire this generation the way the Moon landing did in 1969.

"It's really about making these really amazing prototypes and then selling people on the dream of science and technology and math," Cavalcanti says. "They're all things you can strive to have a career in, and they can be as exciting and entertaining as any sport. You don't have to just play football in high school. You can be a rock star; you can be an engineer."