The sweltering, humid days landscaping for the Palm Beach County Parks and Recreation Department in the 1980s and '90s were tough on Chris Reid's father, Robert. Nights packing shipping crates for UPS at the airport weren't much better.

Picking and pulling, bending and lifting, trimming and twisting. Every day for years and years. The Jamaican immigrant still found time to take his son to basketball and soccer and do yard work at home, but in between jobs and errands, Robert's exhausted, aching body would collapse in a heap. Not much energy was left to play with his three sons or enjoy parks and recreation himself.

But it was worth it to save money to pay for his children's education: to fulfill the American dream—something people used to believe in back then.

"I think he knew even back when he was younger that his choices would pay a physical price in the end," Reid says. "He used to always tell me that he sent me to school to use my mind as a tool instead of just my body."

Now 63 and retired, Robert carries with him the chronic pain of a lifetime of manual labor. Chris Reid made every cramp and ache count, earning a Ph.D. in industrial engineering. He has worked with NASA astronauts and currently, through his position as a human factors & ergonomic engineer at Boeing, is responsible for ensuring its 147,000 workers get home safe and healthy.

His larger mission is to make sure preventable suffering due to overexertion and muscle fatigue, like his dad endured, ends with this generation.

"What I've been pushing is going toward proactive and predictive ergonomics, where we can foresee what's coming up and try to avoid it," he says. "As a paradigm of safety and how you avoid an incident, you try to engineer it out, to begin with."

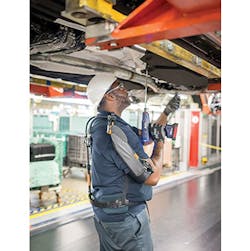

This usually means throwing a robot at the problem, but certain complex tasks, especially wiring up the overhead of a Boeing 777, is something only a highly skilled human can perform.

"If you can't design or automate it out, that's the niche exoskeletons fill," Reid explains.

Since 2012, Boeing has explored industrial exoskeletons. Portrayed in sci-movies as super-powered suits, these wearable tools offer a very real solution to the overexertion injury epidemic surreptitiously stealing company productivity and workers' health. Just as stealthily, several startups have gone into full production on these lightweight wearable support devices that cost less than $5,000 and promise to restore what a hard day's work should earn: a decent quality of life.

"It's a disruptor," says Reid, who joined the program in 2015. "We don't know where it fits in that safety paradigm, but we know it's in there somewhere."

Boeing is a behemoth of a company, and it has a lot of niches. As of late February, they are still running pilot programs to match the right exoskeleton device to the right job, with the emphasis on extraordinary enhancement for safety and performance.

"So far everything looks very promising," Reid says.

Still in the experimental phase, Boeing has not deployed them on the factory floor at any of its seven factories. However, Reid is chairing a subcommittee for ASTM International to develop industry-wide standards for exoskeletons. So the question now isn't if they will be fully deployed, but how soon?

Expense Report

Before looking at the exoskeletons themselves, it's important to understand why companies such as Boeing, Ford, Toyota, and BMW have begun initial testing.

The short answer is that building, assembling or moving anything often requires awkward static postures, repetition of movement, and overexertion. Over time, these increase the likelihood of tissue micro-fissures and musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). And these injuries are equal opportunity offenders. Holding any tool above your head for an extended period, whether it's pruning shears or an impact drill, will tire your arms and sap stamina.

"If there's no time to recover, that's when cumulative trauma occurs," Reid says.

Muscle tissue can withstand a certain weight a certain number of times, each deducting a percentage from the tissue's ultimate tensile strength. This is what Reid and other ergonomists call fatigue failure theory. If you have ever exercised on a bench press, you already know it. If your chest muscles can lift a total of 1,000 lb. before needing to recover, you can lift 100 lb. ten times, or 50 lb. for 20 repetitions before reaching your max. As you get closer to your max, your arms wobble, your body shakes, and the weights start to feel like anvils.

MSDs account for about 30% of all non-fatal workplace injuries, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The 2017 Liberty Mutual Workplace Safety Index puts the direct cost for overexertion injuries at $13.8 billion. In 2007, it was $1.5 billion, according to the CDC.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that MSDs require "a median of 11 days away from work to recover." A rotator cuff surgery, which ranges anywhere from 8,400 to $56,200—according to New Choice Health—could take out a worker for seven months.

A company's rising insurance premiums are only the beginning. Boeing's technicians train for years, even decades, to perform certain operations. If they miss time, they are truly missed.

"When you have to replace them with someone who doesn't have that same experience level, you're going to see potential productivity and quality delays and changes," Reid says.

According to Richmond, Calif.-based Ekso Bionics, makers of the EksoZeroG and EksoVest exoskeletal devices, the U.S. spends $21 billion on workplace injuries that affect productivity. In the construction industry, 20% report severe pain. Using BLS 2016 numbers, that equates to 289,000 construction workers in severe pain right now.

Execution

What's does all this really mean, though?

"[Workers are] going to have difficulties going home lifting their children and being a productive spouse if they're putting their all to a physically taxing job on the line," says Doug Younger, global marketing director at Ekso.

Ekso, founded in 2005 to commercialize robotic medical exoskeletons, aims to demolish the barriers between workers and that all-important quality of life, committing itself to attack this problem at the source via its EksoWorks devices.

The EksoZeroG acts as a third arm and doesn't attach to the person, but to a nearby rail. The 35-lb. tool holder fully supports heavy tools weighing up to 36 lb. In one case, Reno union carpenter Steve Brown saw productivity rise 200 to 300% in an overhead drilling task.

Prior to letting the EksoZeroG carry the burdensome drill, "guys were beating themselves to death," Brown recalls. He calls the device "the number one game-changer I've ever seen in construction."

As the name implies, you do wear the 10-lb. EksoVest, which makes holding a 5 to 15-lb. tool in each arm feel weightless. The series of rotating links and springs transfer torque to parts of the body able to withstand the force, explains Claire Cunningham, user experience manager and technical lead on several of Ekso's medical and industrial exoskeletons.

"The two [sectors] are not exclusive: We are a blend of medical and industrial designers," she is quick to point out.

Arguably, her work with the EksoGT robotic exoskeleton—available to stroke and victims of spinal cord injuries to help them walk upright—provides a more immediate, feel-good public service. The continued development of the EksoVest should not be underscored, as it could impact any of the 1.1 million U.S assembly workers who do overhead work by preventing injury in the first place.

Because the $5,000 EksoVest was built to last five to seven million cycles or up to three years, the cost comes down to about $0.12/hour for a full-time worker. A box of common disposable gloves costs $11.49 on Amazon or just over $0.11.

The United Auto Workers and Ford are both on board, partnering for a 900-hour trial of the EksoVest, which was considered a success with more trials coming.

"If you prevent one shoulder injury, you've paid for the device several times over," says Marty Smets, a Ford ergonomics expert.

And once insurers see a company's claims go down, they can expect to see reductions in premiums to further increase that ROI.

But for non-sociopathic employers, worrying about money should be secondary to the safety and well-being of their workers.

"How many lives have to be negatively affected, how much money has to be spent on these injuries, before we realize it's a problem we could have addressed ahead of time instead of being reactive to it?" questions Zach Haas, Ekso's senior product manager.

Haas equates the importance of exoskeletons to that of common personal protective equipment on job sites and factory floors: steel-toe boots, fall harnesses, hard hats, and safety glasses.

"I absolutely see a future where, just like you have to have your fall harness if you go over four feet, you aren't allowed to pick up that heavy tool until you put on an exoskeleton."

To get to that point, it will take years of medical testing to prove regulations are needed.

Experimentation

The AIFRAME, made by Levitate Technologies, has already earned a CE marking as PPE in Europe and has been demonstrated to counteract fatigue and improve productivity in several trials, both internally and by independent researchers.

The San Diego-based company formed in 2014 made its first sale to BMW's Spartanburg, S.C. plant at the end of 2016. Levitate, which makes 70% of its parts and assembles 100% of the devices in America, is on the verge of moving from sales in the hundreds to the thousands, says Joseph Zawaideh, VP Marketing & Business Development.

The passive AIRFRAME braces the wearers' biceps and a system of pulleys encased in "cassettes" progressively supports the arm as they are raised, propping them up like a spotter at a bench press. The stress normally felt by the shoulders neck and upper back is distributed evenly to padding at the core and hips. It's worn like a hiking backpack and with a one-point release at the belt. It's put on and taken off just as easily.

It was designed specifically to fight fatigue, originally as a tool to support surgeons during long surgeries, and may very well keep many off the operating table.

The device is so light the company considers the actual weight a trade secret. What the company isn't keeping secret is how effective it has been.

At BMW, whereas many as 66 workers are using them at one time, the AIRFRAME has reduced exertion by up to 40%. Zawaideh prefers to use this metric as opposed to specific weight reductions as not to give a false sense of strength, as can happen with back braces. Essentially, these augment stamina, not strength.

An independent Iowa State University study employed electromyography sensors attached to workers' upper bodies to vet the AIRFRAME. The study, conducted at two plants that make farming equipment, used assembly workers, painters, parts hangers, and welders. By getting baselines and comparing levels with and without the exoskeleton, the researchers concluded wearing the exoskeletons reduced EMG amplitudes (the measure of fatigue) by 18 to 39% in the shoulder and biceps. Along the lower spine, they recorded reductions ranging from 7 to 30%.

Along with reducing fatigue and thus the likelihood of MSDs, the AIRFRAME was also shown to improve accuracy and performance.

At equipment manufacturer Vermeer, an expert welder wore the AIRFRAME while using Lincoln Electric's VRTEX virtual welder, which digitally tracks and scores speed and accuracy. He doubled his score of 112 welds in 90 minutes from two days prior without the device.

On a painting simulator, workers could spray 27 to 53% more paint before fatigue set in.

"In lean manufacturing, if you squeeze 1 or 2% more out of job, it's a big deal," Zawaideh says. "This delivered an 8.2% increase in productivity. And not only did he produce more, but he was also more comfortable at the end of the day."

Part of the comfort is the reduced number of touchpoints, which Zawaideh says will keep workers from taking it off in a hot factory during the summer months. And all the medical tests would be for naught if workers won't wear exoskeletons.

"When they first came up with earplugs and steel toe shoes, they weren't welcomed by workers," he says. "Every new PPE tech that comes out, there is an adoption process. Once they get used to it and understand its value, they think it was wrong to be working without this safety product."

Expansion

Exoskeletons allow paraplegics to walk and workers to do their jobs safer and more effectively. The exoskeleton experts see a very near future where they are in every home to help do chores and powered force multipliers, think Ripley's CAT Power Loader in Aliens, could be rented at Home Depot.

Sarcos Robotics' Guardian GT – Big Arm system seeks to fill the 40 to 1,000 lb. "lift gap" between human handlers and forklifts. South Korean and Japanese companies also have prototypes in this domain.

And as talks of what they should be, grow, the amount of cross-pollination with other technologies expand as well.

"In the next five years, we'll see a crossover between disruptor technologies," Reid says. "You'll start seeing exoskeletons mixing with big data and artificial intelligence, health monitoring, and augmented reality."

Every company must come up with their own best way to deploy exoskeletons, if at all. For Boeing, which has the size, applications, and money, Reid says they are taking the safest of routes:

"We're going to throw the kitchen sink at it to strategically and tactically tackle these issues."